Preserving Biological Heritage: The Importance of Type Specimens

Museum collections may seem like they’re just for display, but they often house important biological information (Image Credit: Andrew Moore, CC BY-SA 2.0, Image Cropped)

Last September, the devastating news of a fire in Brazil’s National Museum in Rio de Janeiro hit the world. The fire destroyed most of the collection, including about 5 million insect specimens. Many of the samples were holotypes, a subset of type specimens which are particularly valuable to the scientific world. If you want an indication of just how valuable, some researchers even charged back into the building while it was on fire to rescue these specimens, saving about 80 % of the mollusc holotypes.

This is far from the only case of invaluable scientific specimens being destroyed. In 2017, Australian customs destroyed about 100 Herbarium specimens, including 6 type specimens, that were mailed from the National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) in Paris to the Queensland Herbarium in Brisbane, Australia. Apparently some paperwork was missing, and the declared value of the specimens was $2 (chosen by the institute because it’s simply not possible to declare something invaluable to customs).

But what are type specimens? What makes them so important that people risk their lives to save them from being burned? And why do they always end up at Australia customs?

There are several different kinds of type specimens, the most important being the holotype. When a species is formally described, scientist often base that description on a single specimen. This specimen is supposed to be preserved, to be made available for other researchers, often by placing it in a major museum collection. This is the holotype. It is considered a ‘name-bearing’ type specimens, as it determines the application of a name. For example, if there are uncertainties as to whether a specimen belongs to a certain species, it can be compared to the holotype for that species. This is why type specimens get shipped between institutions around the world so often.

This is your type specimen.

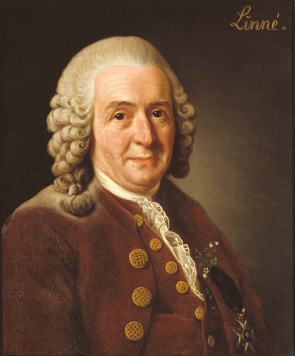

But a holotype might not necessarily have all the characteristics of a species. In this case, the species description is based on several specimens. Often in the past, there was no holotype declared, and and those specimens were used as name-bearers. These are called syntypes. For simplicity’s sake, often a single type specimen will be later declared using the syntypes as a base, and this single specimen becomes the lectotype of a species. The main difference between a lectotype and a holotype is that the lectotype is declared after the original species description is published. Our own species Homo sapiens has a lectotype, the swedish natural scientist and “father of modern taxonomy” Carl Linnaeus (groan, yes, it’s a straight white guy). Thankfully, we don’t have to constantly ship his body between institutions.

Nowadays, a holotype has to be selected upon discovery of a new species. Any other specimens mentioned in order to fill out the description are called paratypes. Paratypes were often collected at the same time and location as the holotype and, in contrast to syntypes, they are not name-bearing.

Holotypes do get lost though. Some species descriptions are quite old, and it’s not unheard of for a student to be searching for an institution that the type specimen was stored, only to find it no longer exists. As mentioned above, they can also be destroyed. In this case, another specimen can become the name-bearing type (neotype), often using the help of existing paratypes or syntypes. However if there are no paratypes, it might become impossible to find a neotype for a species. And without a holotype or neotype, it might become impossible to resolve open taxonomic questions.

Even if a neotype can be located, there’s still a huge loss of data, as Erica McAlister, Senior Curator of Diptera at the British Natural History Museum explains.

“Losing type specimens is devastating. During the fire in Rio last year, anyone with appreciation for what a type specimen is was crying too. Because we realised the importance of what had been lost. We can go back and designate new specimens as neotypes, but how do you know you’re getting the same species? You’re losing biological heritage. So much of this molecular data we are only just beginning to understand how to interpret and use, so the type specimens really are our natural treasures. Every museum around the world, we all get palpitations about type specimen collections and how we use and look after them.”

A sample from the Naturalis Biodiversity Centre in the Netherlands, with the red label indicating that it is a type specimen. (Image Credit: Naturalis Biodiversity Center, CC0 1.0)

So why do we need to ship these specimens around so often? Often, the species might occur in very different places (e.g. Europe and North America), and was then described as two different species with two different names. When it later turns out that it’s actually the same species, the older name is often used for both. Maybe an institute believes it has discovered a new species, or needs to know whether they should merge two existing species into one. So it’s crucial that we protect the existing type specimens. Many type specimens were collected several hundred years ago, some are fossils that are thousands of years old and some are now extinct. We need to do our best to preserve them for future generations!

The fire at the Brazilian museum could probably have been prevented if the government hadn’t drastically cut the maintenance budget in 2014 (and even then, it only received $13,000 of the promised $128,000 in 2018). The earlier mentioned incident with Australian customs is far from isolated, and could have been prevented with more communication between educational institutes and relevant government agencies. Hopefully we can start to develop an appreciation for the repositories of biological heritage that type specimens represent, and prevent further losses.

Kinds of Type Specimens (with Name-Bearers Underlined):

Holotype: a single specimen that is declared as a type in the original species description.

Paratype: Specimens that are used in the original species description alongside the holotype.

Allotype: Specimen of the opposite sex to the holotype, chosen from paratypes.

Neotype: Specimen that is later (after the original species description) declared as the single type specimen to replace a holotype that has been lost or destroyed or when the authors didn’t declare a holotype in the original description.

Syntype: A set of type specimens that are mentioned in the original species description and no holotype is declared, not common practice in modern taxonomy.

Lectotype: Specimen from a set of syntypes that is later (after the original species description) declared as a single type specimen, the other syntypes become paralectotypes after a lectotype is declared.

Paralectoype: after a lectotype is declared, the remaining syntypes are then called paralectotype.

To read our previous interview with Erica McAlister, click here.

Vanessia Bieker is a PhD candidate at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. She study Ambrosia artemisiifolia, an annual weed that is native to North America and became invasive upon introduction to Europe. She uses historic herbarium samples and modern samples from the native as well as the invasive range to study changes over time. Check out her previous articles at her Ecology for the Masses profile here.

Pingback: How You Can Help Out Ecology for the Masses | Ecology for the Masses

Thanks for this very informative article. I work in the area of plant taxonomy. I will share this article with as many people as possible to create awareness about Type specimens.

LikeLike

Very informative. I work in the area of animal taxonomy. I will share and inform others the importance.

LikeLike

Pingback: Collect by all means, but…. | Don't Forget the Roundabouts

Pingback: How we discovered a new giant crustacean on the deepest depths of the ocean floor» Gamers Grade

Pingback: A 'Giant' Crustacean Scavenger Has Been Found out Deep in The Ocean | Vale News

Pingback: A ‘Giant’ Crustacean Scavenger Has Been Discovered Deep in The Ocean – bitarafhaber.net

Pingback: A 'Giant' Crustacean Scavenger Has Been Discovered Deep in The Ocean - extension 13

Pingback: A 'Giant' Crustacean Scavenger Has Been Discovered Deep in The Ocean - Odu

Pingback: A 'Giant' Crustacean Scavenger Has Been Discovered Deep in The Ocean - Xnn News Blog

Pingback: A 'Giant' Crustacean Scavenger Has Been Discovered Deep in The Ocean - a news room

Pingback: A 'Giant' Crustacean Scavenger Has Been Discovered Deep in The Ocean | The Digital News Hour

Pingback: A ‘Giant’ Crustacean Scavenger Has Been Discovered Deep in The Ocean – iDea HUNTR

Pingback: A ‘Large’ Crustacean Scavenger Has Been Found out Deep in The Ocean - Rico Scoop

Pingback: A 'giant' crustacean scavenger has been discovered deep in the ocean - Science News

Pingback: A ‘Large’ Crustacean Scavenger Has Been Found Deep in The Ocean - Lobbiez News

Pingback: A 'Giant' Crustacean Scavenger Has Been Discovered Deep in The Ocean - Trump Won Again

Pingback: A “huge” crustacean scavenger found deep in the ocean – Jioforme |# Daily News Earth

Pingback: A 'Giant' Crustacean Scavenger Has Been Discovered Deep in The Ocean - Science Global News

Pingback: A ‘Large’ Crustacean Scavenger Has Been Found Deep in The Ocean – Tech By Aly

Pingback: A 'giant' crustacean scavenger has been discovered deep in the ocean - Science Daily Press

Pingback: Se ha descubierto un nuevo camarón enorme

Pingback: How we discovered a giant new crustacean scavenging on the deepest depths of the ocean floor | The Natural Health Nut - News

Pingback: How we discovered a giant new crustacean scavenging on the deepest depths of the ocean floor | altnews.org

Pingback: How we discovered a giant new crustacean scavenging on the deepest depths of the ocean floor – SoftMachine.net

Pingback: Voici comment nous avons découvert un nouveau crustacé géant dans les profondeurs des océans - Eric Cooper - Presse

Pingback: Voici comment nous avons découvert un nouveau crustacé géant dans les profondeurs des océans | Mirmande PatrimoineS Blogue